I seem to be stuck in a derivative loop, sharing other people's comedy rather than writing my own.

Maybe I've gotten tangled up in all the overlapping time travel disruptions of the new Star Trek (which I've seen) and the new Terminator (which I'm waiting to see).

Anyway....

This is worth sharing.

Ah, empathy....

Note: Stephan Pastis has a blog!

While I'm on the techie comics roll, here's another funny insider joke from Dilbert:

I had forgotten about User Friendly till I stumbled across it again today.

I used to read the strip daily back when I was on our Integrated Library Systems staff.

I used to read the strip daily back when I was on our Integrated Library Systems staff.

User Friendly is a delight if you're a techie—or if you at least play one in the library. In fact, if you don't have at least a librarian's grasp of tech-ese, you may miss much of the humor.

But it is funny if you get it. Trust me.

For a better sense of what's going on, check out the Character Gallery. The little fuzzy guy on the logo is Dust Puppy. He was "born inside of a network server, a result of the combination of dust, lint, and quantum events."

There's a good archive, including a breakdown by storylines.

Here's the start a storyline called "Greg nukes a customer." It ran on July 6, 7, 9, 10 and 11, 2001:

Click on this first strip, and then you can read through by clicking NEXT CARTOON on the pencil image above the strip.

Click on this first strip, and then you can read through by clicking NEXT CARTOON on the pencil image above the strip.

Have fun,

Mike

In Sunday's New York Times, Motoko Rich has an Ideas & Trends article entitled "Crowd Forms Against an Algorithm."

Rich's starting point is last week's sudden online controversy over a major "cataloging error" by Amazon.com, one which "caused thousands of books—a large proportion of them gay and lesbian themed—to lose their sales ranking, making them difficult to find in basic searches."

In fact, "more than 57,000 titles were affected, including [top-selling classics like] E.M. Forster's Maurice, the children's book Heather Has Two Mommies and False Colors, a gay historical romance by Alex Beecroft."

In fact, "more than 57,000 titles were affected, including [top-selling classics like] E.M. Forster's Maurice, the children's book Heather Has Two Mommies and False Colors, a gay historical romance by Alex Beecroft."

One focus of Rich's article is the massive, almost instantaneous reaction of Amazon's online critics, which ranged from accusations of deliberate, homophobic censorship to arguments that, "while Amazon's intentions may not have been overtly prejudiced, the assumptions underpinning the retailer's categorization of books were still suspect."

What most caught my attention, though, was Rich's additional focus on the fact that the traditional ethical challenges of cataloging are being compounded by today's complex algorithms for categorizing digital content.

"It wasn't the first time," Rich writes, "that a technological failure or an addled algorithm has spurred accusations of political or social bias. Nor is it likely to be the last. Cataloging by its very nature is an act involving human judgment, and as such has been a source of controversy at least since the Dewey Decimal System of the19th century" [emphasis added].

Some folks this past week tried to exonerate Amazon of any intentional discrimination, acknowledging, as did Ed Lasazska of the University of Washington, that there can be all sorts of "unintended consequences of either computer algorithms or human behavior."

As Rich explains, though, others, including some who would not accuse Amazon of outright bigotry, still hold Amazon accountable. Mary Hodder wrote in a post on TechCrunch.com:

The ethical issue with algorithms and information systems generally is that they make choices about what information to use, or display or hide, and this makes them very powerful.... These choices are never made in a vacuum and reflect both the conscious and subconscious assumptions and ideas of their creators.

Dewey is a case in point, says Rich. The DDS is heavily biased toward the dominant white, European-American, Christian culture in which it was birthed. "More than half of the 10 subcategories devoted to religion, for example, catalog Christian subjects."

Most of us 'Net-age library professionals have little direct input into the processes of subject classification and cataloging—either in the library world proper or in the commercially driven world of online search algorithms.

Nonetheless, this one brief article has reminded me that we at least have an ethical responsibility as professionals to be watchful for and, if necessary, to counterbalance both the intentional and the accidental biases of the cataloging and searching tools which we and our customers use.

This includes, by the way, being scrupulously watchful for our personal biases in listening to our customers requests and doing the reference interview. I don't mean just the obvious biases having to do with class, culture, race, religion, etc. I also mean those subconscious biases which can arise out of disinterest in, discomfort with or outright distaste for certain subject areas which customers wish to explore.

For example, I've never had any interest in business. In fact, I grew up with a 1960s liberal kid's cynicism toward what I supposed were the motives of business people. That disinterest in and latent resentment toward the business world means not only that I have remained ignorant of the needs of customers with business questions, but also that I have avoided learning what resources would serve them.

Not very professional on my part. Certainly not good service to my customers.

Rich's article is worth reading in its entirety, and the issue of bias in categorizing and cataloging is an important one for library professionals to keep in plain sight.

One more demonstration that the mandate of the library is to protect everyone's access to all information.

Thanks,

Mike

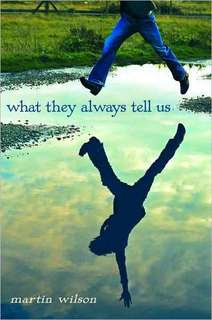

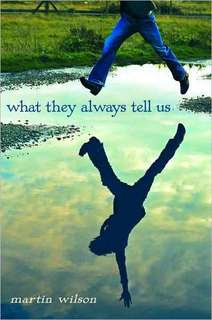

It is so fine when a book's cover grabs you like this one's does. I haven't even read it yet, but I want to.

It is so fine when a book's cover grabs you like this one's does. I haven't even read it yet, but I want to.

And, as I look into the blurbs and reviews, I can see how the image telegraphs the heart of the story.

Here's a blurb from Martin Wilson's blog:

Thoughtful and moving, What They Always Tell Us is a powerful debut novel about the bond between two brothers—and the year that changes everything.

JAMES: Popular, smart, and athletic, James seems to have it all. But the only thing James really wants is his college acceptance letter, so he can get far away from Alabama. In a town where secrets are hard to keep, everyone knows what Alex did at the annual back-to-school party. The only question is why.

ALEX: With his friends no longer talking to him and his brother constantly in motion, Alex is prepared to get through junior year on his own. And he would, if his ten-year-old neighbor, Henry, didn't keep showing up, looking for company. What Alex cares most about is running, and when he's encouraged to try out for cross-country, he's surprised to find more than just a supportive teammate in his brother's friend Nathen.

Lot's of good reviews, too (here and here, for example).

Great work!

When I whined about science project questions not too long ago, an unexpressed part of the complaint had to do with the weird mixture of disinterest and expectation I sometimes get from customers.

As in: "I'm not interested in doing this for myself. I expect you to do it for me."

Back in library school, my fantasy was to work in an academic library. I foolishly imagined that my patrons—what we used to call them before consumerism took over—would actually be interested, not only in learning things from the library, but in learning how to find things for themselves.

Instead, here I am in my ninth year in a public library, flipping burgers for customers.

Well, actually it's not that bad. I've learned to find real satisfaction in those exchanges with customers when I've connected them with essential help or when we both realize we've solved a puzzle together. Such transactions take me back to the best moments of my career as a prison counselor.

Still, my original fantasy continues to distract me: patrons who would "actually be interested...etc."

Here's my curmudgeon's philosophy of library customer service:

My job is to show customers how to use our tools and resources to find the answer—so that I won't have to do it for them next time.

Grumping aside, I actually do believe this.

If customers are dependent on someone else to find them what they need, we aren't doing our jobs as public library staff. Whenever I do a search, whether it's the online catalog or the Internet or our databases or our physical collection, I always "take them along." I turn my computer screen and make them watch while I narrate every step as I do it.

Sometimes it clicks with them, sometimes it doesn't.

Early in my public library career, I was at a regional branch which served kids from three local schools. The buses would dump them all in our parking lot at 3:30 every weekday, and they would tromp in, drop their backpacks with a crash on the nearest table or chair...and head for the computers.

Early in my public library career, I was at a regional branch which served kids from three local schools. The buses would dump them all in our parking lot at 3:30 every weekday, and they would tromp in, drop their backpacks with a crash on the nearest table or chair...and head for the computers.

Once in a while, one of them would come over to the reference desk with homework. Not to do it, but to get it done.

My all time worst case was a middle school girl who said to me, in a voice which was simultaneously annoyed and bored: "I have to do a two-page paper on physics. Would you show me all the websites on physics?"

After I stared at her and got no uptake, I started the usual reference interview, trying to help her narrow and specify her search subject.

"What sort of topics did your teacher suggest?"

"I don't know...."

"Okay...well, what sort of physics topics are you interested in?"

"I don't know...."

It went on like this for almost ten minutes!

Back on my first counseling job out of grad school, I went to my supervisor once to find out how long I should keep trying when a client wasn't making any effort.

"I never work harder than my clients," she said.

That has been my rule of thumb ever since. If I have a client, patient, patron, customer, what-have-you, who repeatedly goofs up but keeps on trying, I work. If I realize the person is waiting on me to "fix it," I stop and wait.

With my prison clients, I could say, "Hey, I go home at 4:30. You have to live here." In the library, "These things must be done delicately."

"Okay," I said to the middle schooler. "Let me get you signed onto a computer, and I'll show you how to search Google."

A somewhat better case occurred at the same branch. A mom came up to the desk with her kid in tow. (He was staring longingly at the row of PCs across the room).

A somewhat better case occurred at the same branch. A mom came up to the desk with her kid in tow. (He was staring longingly at the row of PCs across the room).

"He has to find three articles for a biology paper," she said.

"Okay," I replied, speaking to the kid. "What's your paper topic?"

"Planaria," said the mom.

"Planaria," said the mom.

"Ah." I turned the screen so the kid could see it. "Maybe you could search our online science database."

Mom: "Would that have articles he could use?"

Me (to kid): "Yes, it has full text articles from dozens of different science research journals. Let me show you how to search it."

Finally the mom caught on.

"Listen to the man!" she said, swatting her kid on the shoulder. "He's trying to help you." She pulled a magazine out of her bag and walked away.

I don't remember whether I got very far with the kid, but at least I now had a "teaching moment."

The best recent example was actually that same science project question I complained about. Granted, the kid with the homework wasn't present. However, the mom and I really engaged with each other in redefining and targeting the search. She was happy with the titles I found, and she was particularly pleased to learn about our online databases—especially the fact that her daughter could continue the research remotely from her home PC.

What I have to keep reminding myself is this:

- I'm an old guy who's been working since 1968

- It's too early to retire (in this economy, it may always be *groan*)

- What I most want to spend my time on now—reading, writing, coffeehouse conversation, sitting in the sun—I'm unlikely to get paid for

- I don't want to have to satisfy an editor or a tenure committee to get paid

- I am actually very good at customer service (I know how to put the curmudgeon on hold and be a real human being with my customers)

- Sometimes I enjoy it.

Hmmm.... Does this mean I asked for the job?

Just for fun—don't...*ahem*...take this as a comment on my own organization—I've added a Dilbert Widget to the sidebar. It's down below the links.

Enjoy.

I used to read the strip daily back when I was on our Integrated Library Systems staff.

I used to read the strip daily back when I was on our Integrated Library Systems staff. Click on this first strip, and then you can read through by clicking NEXT CARTOON on the pencil image above the strip.

Click on this first strip, and then you can read through by clicking NEXT CARTOON on the pencil image above the strip.

In fact, "more than 57,000 titles were affected, including [top-selling classics like] E.M. Forster's Maurice, the children's book Heather Has Two Mommies and False Colors, a gay historical romance by Alex Beecroft."

In fact, "more than 57,000 titles were affected, including [top-selling classics like] E.M. Forster's Maurice, the children's book Heather Has Two Mommies and False Colors, a gay historical romance by Alex Beecroft." It is so fine when a book's cover grabs you like this one's does. I haven't even read it yet, but I want to.

It is so fine when a book's cover grabs you like this one's does. I haven't even read it yet, but I want to. Early in my public library career, I was at a regional branch which served kids from three local schools. The buses would dump them all in our parking lot at 3:30 every weekday, and they would tromp in, drop their backpacks with a crash on the nearest table or chair...and head for the computers.

Early in my public library career, I was at a regional branch which served kids from three local schools. The buses would dump them all in our parking lot at 3:30 every weekday, and they would tromp in, drop their backpacks with a crash on the nearest table or chair...and head for the computers. A somewhat better case occurred at the same branch. A mom came up to the desk with her kid in tow. (He was staring longingly at the row of PCs across the room).

A somewhat better case occurred at the same branch. A mom came up to the desk with her kid in tow. (He was staring longingly at the row of PCs across the room). "Planaria," said the mom.

"Planaria," said the mom.